Is SBA Bureaucracy Bankrupting Small Businesses? It’s Not That Simple.

At the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in spring 2020, business owners were panicking at the thought of going under. For many, federal financial assistance programs provided by the U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA) felt like a lifeline.

In the years that followed, one of those programs, the highly publicized Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), has been widely lauded for providing stability for the U.S. economy and keeping companies in business through loans that were largely designed to be forgiven.

The PPP was spun up in April 2020; but it wasn’t the first to offer assistance to business owners. An earlier SBA program, Economic Injury Disaster Loans (EIDL), was in place for business owners concerned about their survival at the very start of the pandemic. The longstanding program has been iterated over the years and, in March 2020, it was quickly retrofitted once again to provide an initial stopgap source of pandemic financing for millions of businesses – including many CPG startups.

But unlike PPPs, EIDL loans weren’t designed to be forgiven, and many business owners feel hamstrung. The EIDL loan terms restrict these businesses’ ability to take on new investors, and the quick deployment of the program at the onset of the pandemic – which saw the SBA, rather than traditional loan providers, finance the loans – has left business owners facing the prospect of navigating a federal bureaucracy, rather than a comparatively simple banking setup, to try to alleviate the pressure.

For business owners, the terms of the EIDLs allowed them to keep their businesses open, but not to grow, they say. For early-stage CPG brands, the path to profitability most often comes as a company grows and scales up, which can bring down average unit costs and increase profits. Unfortunately, that growth often starts with investment – something they can’t easily access under EIDL terms.

Beyond that, the demands of the pandemic were such that remaining open was cost-intensive – and operating costs themselves have increased due to pandemic-related labor shortages, service interruptions and materials costs increases.

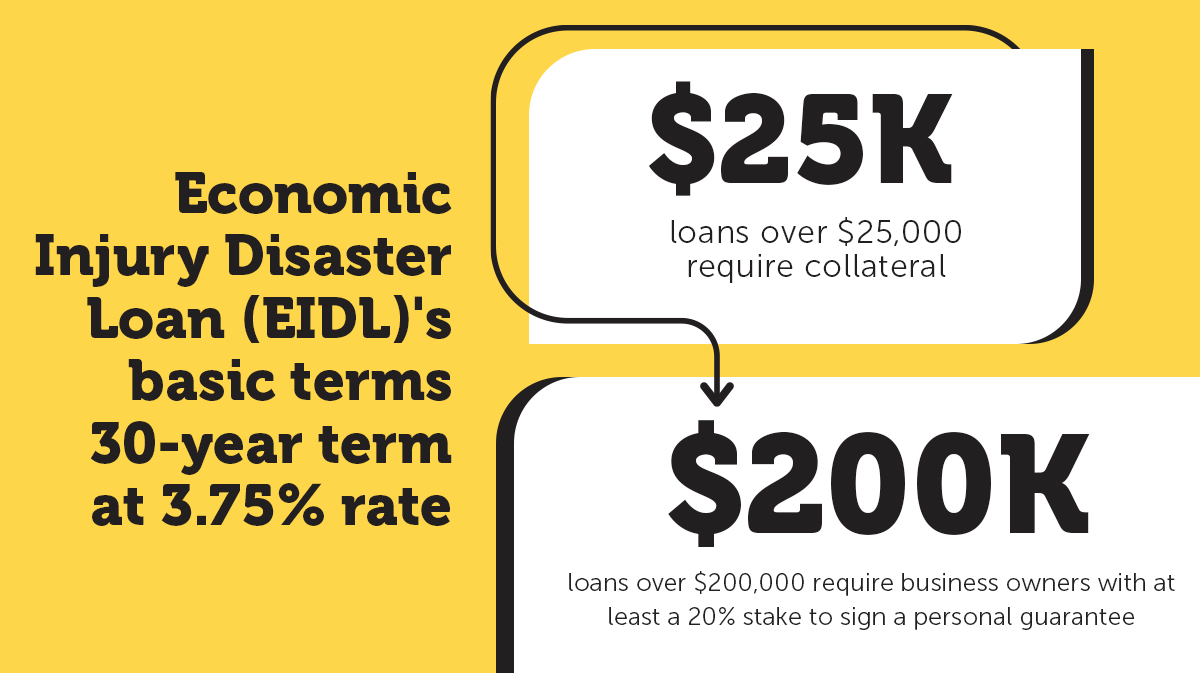

The EIDL program allowed small businesses owners to borrow anywhere from $10,000 up to $2 million (the program originally capped loans at $500,000 but was extended in October 2021); the funds were intended as a substitute for working capital, helping keep the lights on during the initial lockdown period, keep workers employed as well as fund safety-related needs such as purchasing protective shields and providing employees with personal protective equipment (PPE).

But the costs of protective equipment, insurance and COVID safety processes all added up, according to one food company owner Nosh spoke with – and now there’s no good way to pay back what was lent out.

Additionally, EIDLs of more than $200,000 required personal guarantees from anyone holding more than 20% share of the business – something that’s vexing because it grants the federal government permission to not only liquidate the business, but also the owner’s personal assets if the loan goes into default. Those guarantees have also become a barrier to those looking to sell their businesses as the process and timeline to secure SBA approval and not risk a technical default can leave a deal dead on the table.

Nosh spoke with several food and beverage business owners to try to determine the extent of the pressure EIDL loans are bringing to the industry; they all refused to reveal their identities due to fears over their loans being called by the SBA, and the personal guarantees endangering their own financial stability as well as their businesses’.

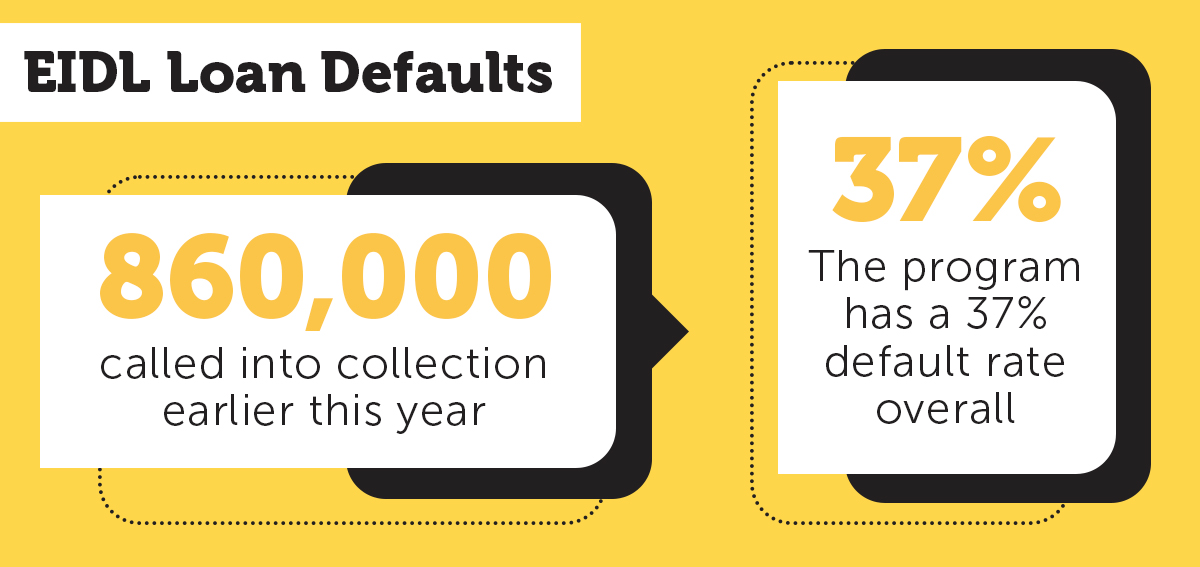

Earlier this year, the SBA executed a round of audits on the EIDL program and sent a whopping 860,000 loans to the Department of the Treasury for collection, according to the Wall Street Journal. An Inc. report from May notes that the program has an estimated default rate of 37% and could likely increase as deferred payment plans begin to expire.

Certainly, the loans themselves came with generous repayment terms: many owners were able to defer payments until this year, and the interest rate of 3.75% over 30-years compares favorably to current business lending rates that are nearly double. Additionally, the program allowed for hardship extensions that have allowed recipients to make lower monthly payments.

But the caveats weren’t in place and for those who acted fast during the initial lockdown period and took funds from the EIDL program; they are now facing the sobering reality that they’re stuck in a tough spot. Repayment itself is not the issue: These small business owners feel the required personal guarantees have created a massive hurdle to growth, leaving them with little options to dig their way out of the debt without risking bankrupting both their businesses and themselves.

EIDL’s Infrastructure Issue

The EIDL program was designed to support small businesses in the wake of unforeseen events such as natural disasters. As COVID lockdowns spread, the program was quickly stood up for pandemic assistance, though even the SBA soon understood it would need a more substantial vehicle to support the volume of businesses seeking assistance. That eventually led to the creation of PPP, explained Chris Kane, a partner at Adams and Reese who has worked with the EIDL program since the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

Four years later, and after a period of deferment, EIDL recipients are beginning to repay their loans. Multiple CPG business owners have told Nosh that they only recently became aware that the terms agreed to in 2020 have forced them into a corner, unable to continue growing.

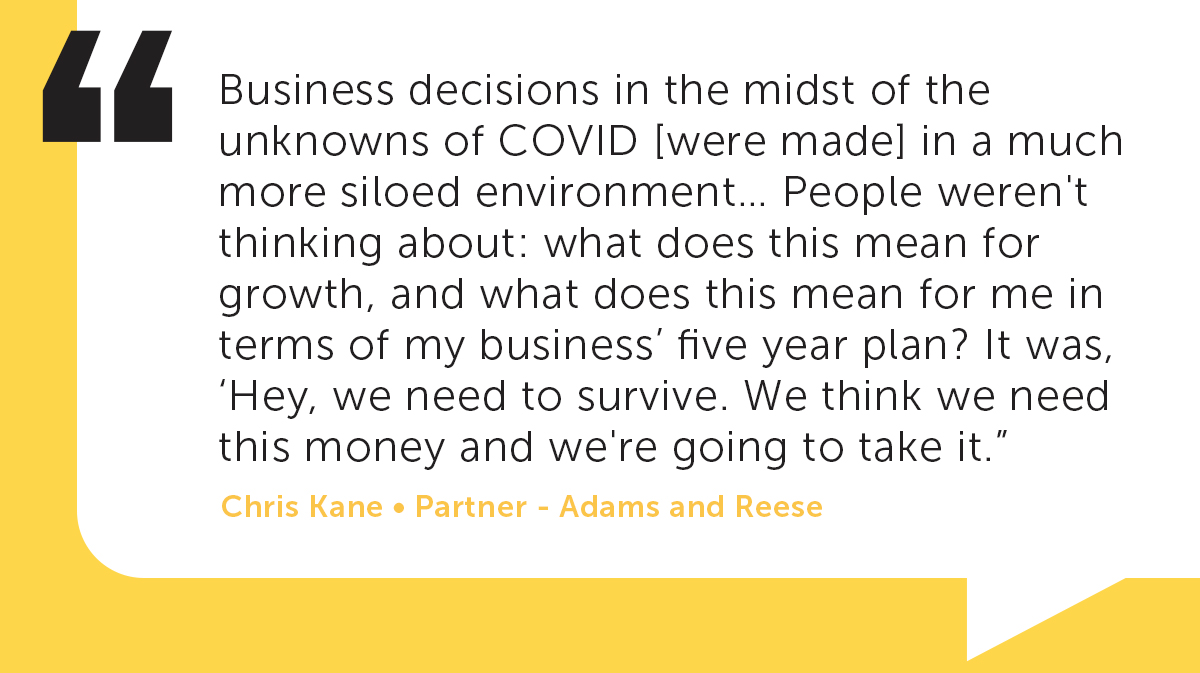

“The concern I had then, and the concern that we see now, is that folks that were making business decisions in the midst of the unknowns of COVID [rightfully so, but] in a much more siloed environment,” explained Kane.

“People weren’t thinking about: what does this mean for growth, and what does this mean for me in terms of my business’ five year plan? It was, ‘Hey, we need to survive. We think we need this money and we’re going to take it.”

Desperation was everywhere at the start of the pandemic, and while Congress quickly authorized the funding, the SBA still had to retrofit the EIDL program to meet the needs of small business owners at that time. Per the existing EIDL infrastructure, the SBA serves as the lender – a role that is traditionally filled by a bank, even within other SBA-backed lending programs. But for a service designed to quickly allocate cash during dire emergencies, it is necessary for the SBA to fill this role, remove intermediaries and be able to quickly wire out cash.

It was effective – the SBA was able to lend upwards of $390 billion to small businesses via EIDL during the onset of the pandemic – the most it had ever lent under the program; in only three weeks it had allocated the sum of nearly “eight life-spans of SBA disaster lending,” Kane said.

But as Kane notes, this structure has also contributed to many of the fundamental challenges EIDL recipients now face. “You’re dealing with a government entity that is not set up to be a loan processor,” he said.

Like any business loan, lenders need to hedge against risk. The SBA required collateral for loans over $25,000; for sums over $200,000 where the business owner also held at least a 20% stake in the company, they had to sign a personal guarantee, signifying they would service the loan even if their business no longer could. That means if their business failed or the borrower defaulted on the loan for any reason, the SBA could come after their personal property and assets.

But there is another catch. Even for a company with multiple shareholders all owning at least 20%, some business owners Nosh spoke with said guarantees were assigned to only one individual signatory. That’s a problem because it means whoever handled the loan paperwork is on the hook for the whole business.

“In the height of the EIDL-COVID world and the ever-changing rules, the underwriting and due diligence was… what’s the polite way of saying this…not, perhaps, the best,” Kane said, while noting that in his 15 years dealing with the program, he has never seen money distributed from this program at that “speed and velocity.”

Raising Capital Roadblocks

As is standard practice with business loans, EIDL recipients are required to notify the SBA ahead of any changes in company ownership including taking private equity or venture capital investment. But the SBA isn’t a bank, and communication is much more complex. There is a portal where recipients can submit requests, but turnaround timelines for a response are inconsistent at best.

Those gaps in communication are more than just an annoyance. A handful of small business owners holding EIDL loans told Nosh they were unaware they needed to contact the SBA ahead of raising money. One founder, who gave up at least 20% of the company to a VC firm to help fund growth, has found themselves in a bind. They’ve technically triggered the SBA’s personal guarantee requirement, but have been told by the SBA the VC firm can’t supply a personal guarantee.

However, the SBA told Nosh that it will “consider changes of ownership involving investment from a venture capital firm. In general, buy-ins and buy-outs will require a paydown or payoff of the Covid EIDL loan. Each situation is unique, and SBA would need to review the details of the deal to determine if a paydown or payoff is required. Depending on the amount of ownership change, SBA may also require a guarantee from the new owner, which could include the venture capital firm.”

Either way, with cash tight across the CPG investment landscape, these loans have added another layer of complexity to growth.

In Arrears

While the SBA has referred an increasing number of the loans for collection, it’s not necessarily fatal, notes Joshua French, a partner at the law firm Nutter. French believes it is possible for businesses that are in technical violation of their loan agreements over new financing arrangements to backtrack and receive SBA approval, but that it will hinge on their ability to find the right contact. In the best case scenario, he said the borrower would be able to get a letter stating that they’ve corrected the issue and it’s all “water under the bridge.”

Backtracking and asking for forgiveness “is uncomfortable” but necessary, Kane agreed. That’s easier said than done when the federal bureaucracy is factored in. Both Kane and French agreed that in the meantime, borrowers in technical default should just continue to make their payments and continue with business as usual.

“I don’t think it’s a high priority item to seek out companies that got an EIDL loan and then subsequently took in cash from an investor and used it to grow the business,” said French. “I don’t see the SBA trying to find these types of businesses that are in technical breach and call their loan, because it’s just going to result in more challenges collecting on that [debt].”

Turning Debtors into Collectors

Recognizing the difference between EIDL and PPP, Rep. Roger Williams (R-Texas) made a proposal to forgive the loans, but it has failed to gain traction in the U.S. House of Representatives, despite arguments that the administration has taken on more than it can handle. The SBA itself explored selling off the EIDL portfolio earlier this year, but those plans were dashed when it was estimated that it could cost taxpayers upwards of $121 billion.

“This is a loan that is to be paid back, no different than any other debt,” Kane said.

But collecting on those loans – remember those 860,000 defaults – is proving to be a challenge for the EIDL loan facilitators. According to a recent article in the Jacksonville Business Journal, the SBA has begun asking defaulted borrowers in the midst of bankruptcy to assist with their own collection process. The report claims the SBA has contacted numerous borrowers, asking if they would sell off the collateral used to secure the loan and then hand the proceeds to the SBA.

The SBA explained in those requests that the size and scope of the EIDL program has left them without the infrastructure to take, process and sell collateral without taking on expenses that haven’t been authorized by Congress.

“The SBA has the right to call your loan [if you are in technical default], but realistically, they’re not going to do that unless they actually are afraid that this is a company that’s about to go under, or is about to suffer some other loss that puts its position, vis-a-vis the loan, in a much worse place,” French explained.

Still, slow-walking a loan might not be the best idea: according to the Journal, other borrowers have been subject to an additional 30% collection fee by the Treasury for defaulted loans.

Paying Off and Getting Out

For those wanting to sell their business outright, the timeline and ability to communicate with their lender poses an additional challenge. According to Kane, the SBA will assess those requests based on need.

“I have been told by folks at the SBA what they will consider is, if there is an ownership structure change or a sale of a company that is driven by hardship – so the company is going to go bankrupt, it’s a desolate situation, and somebody is willing to come in and buy it and maintain the company, maintain the jobs, whatever it might be – that story is going to be way more sympathetic for the SBA to provide the consent and they’ll view that as a hardship exception.”

One business owner who received $2 million in EIDL loans, and agreed to speak off the record, has been in the process of trying to sell their company but has faced challenges due to the personal guarantee requirement. Now that they have found an interested buyer, getting the EIDL loan out of the way and personal guarantee removed has become the largest hurdle to the deal.

“The volume of administrative mess that these guys have to deal with, and their responsiveness becomes a challenge,” Kane said. “A lot of small businesses get frustrated with that, even though, there’s a portal and there’s an ability to communicate – It’s not like going to your local community bank and going to sit down with Mr. Johnny and you’ve worked together for 20 years, get a cup of coffee and say, ‘Man, this is my situation.”

Companies can submit for a payoff letter as would be required by any other business loan, but those requests will go through the online portal and subject their deal to an indeterminate timeline. Otherwise, business owners can thumb through the SBA’s directory of 1-800 numbers and cross their fingers that the person who picks up has the authority to assist: “it’s going to be hit or miss,” French explained.

“In my mind, it’s no different than any other debt that a company would have… it’s just a matter of finding the right person,” French concluded.