Coffee: Study Details Links To More Steps, Less Sleep, Heart Health

Caffeine’s impact on health has been the subject of numerous scientific studies trying to answer the question: Is drinking coffee good or bad for people?

A recent study published in The New England Journal of Medicine on Thursday suggests that coffee consumption throughout the day increases physical activity while also negatively impacting a person’s sleep at night; yet, the impact of coffee on the heart are mixed.

The prospective, randomized, single-center study was conducted by the University of California, San Francisco and tracked the effects of caffeinated coffee on a person’s heartbeat, activity level, sleep minutes, and glucose levels over a 14-day period. The 100 participants represented a cross-section of ages from 20 years old to 70 years old and were demographically “representative of the population of the city of San Francisco.

Participants’ steps and sleep were monitored with Fitbits while an electrocardiogram device tracked their heart’s rhythm and a glucose monitor noted blood sugar levels. Each participant was instructed daily by text message to either consume a caffeinated coffee that day or to refrain from caffeine intake.

Coffee Equals More Steps, Less Shut Eye

On average, participants who were instructed to drink at least a cup of coffee during the day took 10,646 steps compared to 9,665 steps taken on average on days where coffee was avoided, the study reported.

In past cohort studies, coffee’s impact on increased activity has been used to support the theory that it leads to better health outcomes like lower mortality rates and overall longevity. According to one study linked in the results, increasing one’s activity by about 1,000 steps during the day can be linked to a 6% to 15% reduction in mortality.

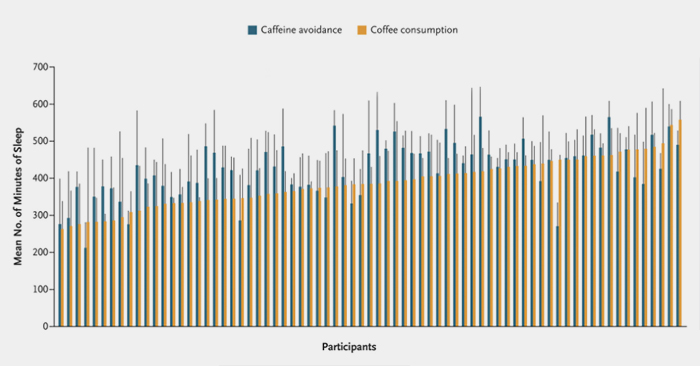

However, the trade off comes with coffee’s negative impact on sleep. On days when a cup of coffee was consumed, participants averaged 397 minutes of sleep as opposed to 432 minutes on coffee abstinence days. The study cited other scientific research which has shown that losing over an hour of sleep at night increases negative health outcomes like cardiovascular disease, cancer and cognitive function, but there is less evidence on how 30 minutes of lost sleep impacts a person’s general health.

Due to the fact that Fitbits are not clinical-grade devices, researchers acknowledged that sleep durations should be considered estimates and other markers of sleep quality were not measured.

The correlation between sleep and coffee must be determined individually from person to person, the study’s researchers reported. “The results raise the possibility that coffee consumption had little effect in participants who were fast caffeine metabolizers, whereas those who were the slowest caffeine metabolizers had the most exaggerated effects.”

Heart Rhythms And A Cup ‘O Joe

Researchers also analyzed how drinking at least one cup of coffee during the day can affect a person’s heart rate. By monitoring participants’ heart rhythms, researchers attempted to find a correlation between arrhythmias, or irregular heartbeats, and coffee consumption.

The study reported that there was “no evidence of statistically significant relationships between coffee consumption and the frequency of premature atrial contractions (PACs or extra heartbeats that begin in two upper chambers of the heart),” which was consistent with findings from other scientific research on the subject. Yet, there was an increase in daily premature ventricular contractions (PVCs or extra heartbeats that begin in two lower chambers of the heart) among people who consumed more than one coffee drink per day.

“These can cause symptoms, and, in some people, a higher frequency can lead to the development of heart failure,” said Dr. Gregory Marcus, a cardiologist and professor of medicine at the UCSF. “We observed about 50% more PVCs on days when people were randomly assigned to consume coffee, and those who drank more than one cup had a doubling of their PVCs.”

When asked if PACs or PVCs were more detrimental to one’s heart health, Marcus said, “rather than characterizing the heart as working harder, I would say that PVCs can be uncomfortable, and, over time in some people (but not everyone), set up a cascade of signals in the body that can ultimately lead to a weakening of the heart.”

However, Marcus pointed out that more physical activity is good for heart health and the study could not determine the apparent effects of how caffeine’s impact on energy and activity may cancel out its effect on the heart.

The study went on to suggest there might be a correlation between a regular coffee drinker and lower risk of atrial fibrillation – the most common form of irregular heartbeat – due to the anti-inflammatory properties of the drink helping heart functioning, but more research was needed to prove that out definitively.

Although hard to determine in this one study, Marcus pointed out that genetics plays a role in caffeine’s impact on the body.

“First, those who metabolized caffeine more quickly experienced the greatest increase in PVCs when exposed to coffee,” he said. “In contrast, those who metabolized caffeine the slowest had the worst detriments in sleep- those who metabolized coffee quickly had no detectable relationship between coffee and sleep.”

Marcus described the report’s “big picture finding” to CNN saying “that there isn’t just one single health-related consequence of consuming coffee, but that the reality is more complicated than that.”

On a more reassuring note, Marcus noted “individuals can be reassured that there’s certainly no imminently dangerous effects of drinking coffee.”