How USDA’s Organic Fraud Rule Could Impact CPG Brands

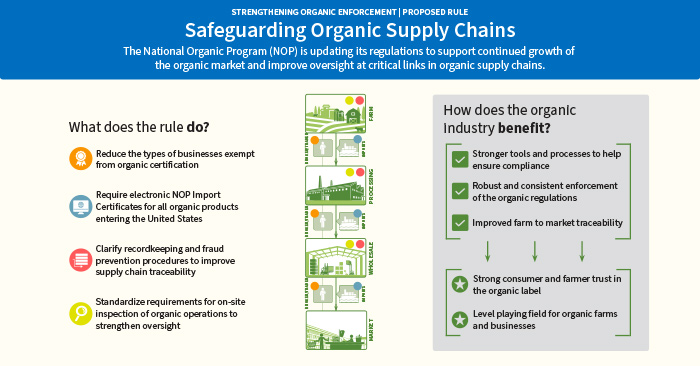

A proposed rule by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), ‘Strengthening Organic Enforcement,’ aims to curb organic fraud via more oversight of the organic marketplace, including production, handling and sales. If implemented, it would be the largest update to organic oversight in 20 years as the USDA seeks to improve transparency in organic products. It’s a move that advocates say is sorely needed, but may result in thousands of new certifications required by farmers, processors and brokers.

The rule was submitted to the Federal Register last Wednesday and is open for public comment until Oct. 5.

According to a USDA spokesperson, the rule would apply to any food and beverage brand purchasing or selling organic ingredients and products, except companies with under $5,000 in gross annual organic sales. In the rule, the USDA justified the changes, noting that organic supply chains have become more complex since the National Organic Program (NOP) was established in 2000.

To better manage the supply chain, the rule would standardize organic certificates and mandate them for all imported organic products. While the current rule does not require certifications for businesses that transport and deliver organic crops, the new rule would also require anyone handling organic agricultural products, including those processing, packaging, repackaging, or labeling products, to obtain certification. Retailers and operators only transporting or storing organic items would be exempt.

“Organic products and ingredients are often handled by dozens of operations, including many uncertified entities, on their way to the consumer,” the rule notes. “This may expose organic products to greater risk—including opportunities for mishandling and fraud.”

The rule would also increase inspector qualifications and update their inspection protocol, requiring annual inspections for every organic operator and unannounced visits for 5 percent of them. Additionally, organic producers would need to implement fraud prevention programs and report more supply chain data. Although the rule would also change how producers calculate organic content in products, Gwendolyn Wyard, VP of regulatory and technical affairs at the Organic Trade Association (OTA), said this change should not impact brands.

According to the USDA, the proposed rule would result in further organic certification from approximately 19,484 farmers and 10,167 small processors in addition to food wholesalers, brokers and handlers. The USDA provided an impact analysis which estimates $56 in added annual costs for existing organic companies under the new rule, with $31 for labeling and $25 for supply chain traceability and fraud prevention programs.

Those companies who have to seek certification for the first time would pay larger upfront costs. The USDA estimates that organic certification fees can range from a few hundred dollars to several thousand dollars. Dan Kaatz, quality systems manager at Nature’s International Certification Services (NICS) estimates it would cost $1300 to certify one location of an organic food processor with additional fees depending on the number of locations and annual organic sales. However, this pricing isn’t standardized throughout the industry, with other certifiers operating on more of a base-fee model without tiered increases.

Given these costs, some processors may simply choose not to pursue certification, he noted.

The USDA does have a program to help cover organic certification costs, but the agency announced this week that reimbursement would be reduced to 50 percent through 2023, down from 75 percent. The decreased coverage, the agency said, will allow more operators to receive assistance moving forward.

The move comes as the pandemic has been accompanied by an uptick in organic purchases, according to the OTA, which represents 9,500 organic companies. Organic food sales were up 4.6% in 2019, hitting $50.1 billion in sales and outpacing conventional food by 2%, according to the OTA. Wyard said the increase is due to health concerns and also because consumers are increasingly engaged in climate change and sustainability and seeking brands addressing related issues.

“Expectations are that demand will continue to be strong as consumers continue to search out the most clean and healthy products,” said Wyard. This growth is part of the impetus for the legislation, which would make tracing ingredients easier for CPG brands, a USDA spokesperson told NOSH.

While consumers may only think about the end products they purchase in stores, according to Liz Figueredo, technical manager at organic certifying body QAI, owned by NSF International, CPG brands aren’t the catalyst for the rule. Instead, Figueredo said further enforcement is needed for operators importing, brokering and trading large quantities of “organic” ingredients, especially grain and oilseeds such as peanut, rapeseed, soybean and sunflower seed.

“This has been where fraud has been uncovered in the past,” Figueredo said. “Increasing transparency will make it easier for food and beverage brands to keep an eye on ingredients all the way back to the farm.”

The USDA estimates that counterfeit and pirated organic goods comprise 2 percent of global trade, amounting to $30 million in illicit organic import costs and $79 million via domestic agriculture. The new rule will reduce organic fraud occurrences to 1 percent, the USDA said, which over the next 15 years would save the industry $725 to $985 billion, or $80 to 83 million annually.

The OTA last year established its own organic fraud prevention program, which the USDA cites in its rule as a prime example in helping to combat fraud. The program helps companies verify their suppliers and implement an organic fraud prevention plan. Training for the program was released in March, with 57 initial participants, including organic brands Lundberg, Beetnik, Handsome Brook Farms, CLIF Bar and Ardent Mills.

“Organic companies recognize the need to implement fraud fighting measures and the program offers training and a guided process for doing so,” Wyard said.

Jordan Czeizler, CEO of egg brand Handsome Brook Farm, noted that despite the high cost of organic land and feed in the egg business, the organic seal is crucial to the brand’s value.

But while this seal is valuable, David Perkins, founder and CEO of frozen brand Beetnik, added that more can be done to expedite organic labeling regulation for small companies. Getting these certifications can be an arduous process, especially for companies that have never been through the process before; it’s unclear how a rush of thousands of new companies seeking certification could impact turnaround times. For example, after retailers and states introduced new regulations surrounding the labeling of GMO products, brands reported lengthy waits to receive certifications.

Kaatz added that NICS is preparing for even more certification requests from processors, noting that the USDA may be underestimating how many aren’t yet certified. However, he said, the certification process for these operators is straightforward, plus the rule isn’t yet finalized.

Additionally, the USDA regulations wouldn’t solve all issues. Czeizler also believes that organic has come to develop a halo effect, indicating a wealth of benefits to consumers that don’t always ring true. For example, for eggs, the company would like to see the USDA call out both organic and “pasture-raised” as the “gold standard.”

“Without the environmental aspect, you are only halfway to where you should be in this category,” he said.