Sustainability On-Pack: Commitments To Cut Carbon Take On New Looks

Demand for better-for-the-planet products continues to drive new product innovation, and has led to the creation of entirely eco-conscious platform brands. At the same time, approaches to sustainability have become more nuanced, making marketing increasingly important. Brands are trying to find new ways to accurately communicate their environmental commitments, and for many, that has required the development of a new set of certifications that extend beyond the older, established classifications.

The majority of consumers have an interest in how these commitments are relayed: 55% say they are more likely to buy a food item if it includes a sustainability claim on-pack, up 4% since 2019, according to a survey from ingredient supplier Cargill.

Certifications like USDA Organic, Fair Trade, Non-GMO Project Verified and the “chasing arrows” recycling symbol have, for several years, been the most recognizable marks that brands are “up to good.”

In some cases, new certifications might extend the causes represented by their predecessors. Nevertheless, a brand’s mission and a label’s messaging don’t always align, driving some brands to look at the newcomers as they sort through what is key on-pack to best represent their mission to the consumer.

Right now, the preeminent sustainability mission for both brands and consumers is cutting down carbon emissions, the most common greenhouse gas (GhG) produced by humans. But the methods for doing so, and claims to reflect that mission, are getting more refined. From how ingredients are grown and processed to how products are packaged and shipped, several new certifications have emerged that track carbon impact at each step on the route to market.

In the past two years labels such as Climate Neutral, Upcycled Certified and Land to Market have been introduced to the CPG world. While none of these labels overtly detail a product’s impact in reducing carbon emissions, each approaches the cause at different steps along the supply chain. Beyond that, these movements have evolved from self-made eco-claims into formal, third-party vetting systems.

What does it mean to cut carbon?

Carbon emission reduction is generating the most interest for consumers, and leading the growth of climate related commitments for brands, but the cause is not always as clear-cut as a single new symbol.

Take the big companies: while Mondelēz and Nestlè have publicly committed to achieving net zero emissions by 2050, others are working toward different ends – implying that they’re working on reducing their carbon footprint by launching upcycled product lines, as is the case with Dole, or highlighting their use of sustainable agricultural methods like General Mills. In March, General Mills dedicated its booth at National Products Expo West to highlight its mission to convert one million acres of farmland to regenerative agricultural practices by 2030.

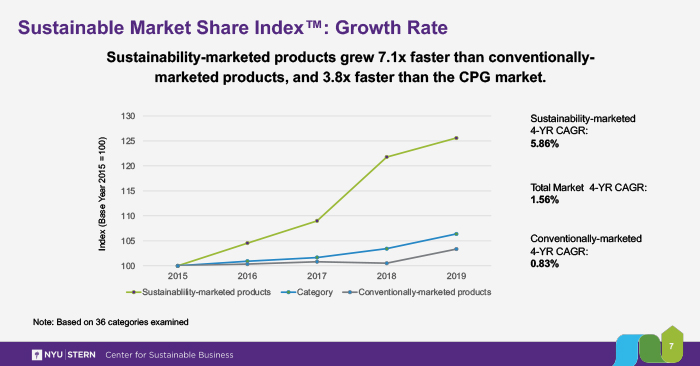

While these interests benefit the planet, they also benefit business. NYU’s Stern Center for Sustainable Business, in partnership with market research firm IRI, found that sustainably marketed products accounted for almost 55% of growth in the CPG industry in 2020 and also noted that those products grew seven times faster than offerings that weren’t marketed as sustainable.

At the entrepreneurial level, some brands are pioneering their own certification methods to cut through the clutter. Planet FWD, the sister company to climate neutral cracker brand Moonshot Snacks, recently launched its own third-party certification program to help other companies work toward offsetting their impact on the environment. In May, the program announced it had raised $10 million to continue developing its platform and enable more brands to track carbon output.

Certifications like Carbon Neutral, Climate Neutral and Planet FWD all allow brands to work backwards and implement environmentally positive solutions at any stage of their operations to reduce and offset their carbon footprint. According to Climate Neutral Certified, it has 300 certified brands working toward offsetting and reducing emissions and it expects to offset one million tonnes of emissions in 2022 alone.

Interest in this specific approach is also growing, according to Innova Insights, which tracked a 27% increase in ‘reduced carbon’ claims among new food and beverage products since 2017.

To earn these certifications, a brand must first assess its impact, which is calculated by a team of third-party experts. It is then provided with reduction targets, when possible, and “carbon credits” to offset emissions when balancing reduction with continued operation reaches its limit. Earlier this year, Riff became the first energy drink to earn a Carbon Neutral certification for its Energy+ line of upcycled, sparkling cascara-based beverages.

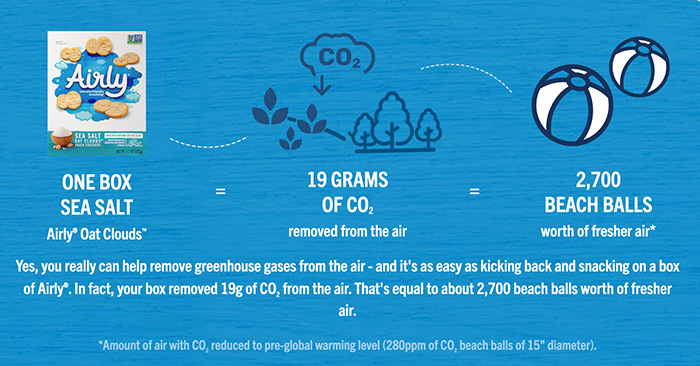

But not everyone is buying into new certifications. Airly, a self-proclaimed “climate-friendly” cracker brand, and product of Post Holdings’ accelerator program, said it has chosen to not pursue any third-party certifications because it believes none of the existing programs fully reflect its cracker’s carbon impact. Instead, it has designed branding assets to reflect the mission and depth of that impact.

What’s working at the ground level?

Beyond carbon emissions, upcycling and food waste reduction are another fast-growing way brands are tackling carbon reduction. Organic and Fair Trade, the original ground-level certifications, aren’t the only area of focus anymore – now there’s an aspiration to pull waste out of the system as part of the process.

Upcycled Certified, the third-party program that certifies products made from repurposed imperfect produce, byproducts or sidestreams, said that since its badge first made it on-pack and on-shelf early last year, it has seen higher than anticipated demand. Upcycled Certified now projects that the program could help divert 703 million pounds of food waste from landfills each year. It’s a small dent in the problem, however: according to the USDA, food waste emits 170 million metric tons of carbon dioxide GHG annually, an output equal to that of 42 coal-fired power plants.

Innova Market Insights has also tracked an increased presence of upcycled and waste reduction claims, which have risen 46% among new food and beverage product launches since 2017.

These claims have become more than just the platform for entrepreneurial brands like Renewal Mill, Barnana and Spudsy. Upcycling has evolved into a movement embraced by both startups and global legacy brands such as Dole and Nestlé. CB Insights reports that corporate concerns over food waste are trending upward. According to its metrics, the term was mentioned almost 200 times on earnings calls between 2018 and 2020.

Why is Sustainable Sourcing different?

Fair Trade has long been the call-brand certification for products that are committed to producers, the environment, and a social cause – but now, that, too, is evolving. Some consumers are looking for “Sustainably Sourced” brands, a claim that has taken on broader meaning to encompass a wider range of agricultural practices. One downside is that it’s self-made, rather than certified – but that is changing.

Some certifications, like Rainforest Alliance and Regenerative Organic Certified, are indicative of sustainable sourcing – but the term could simply be so broad as to be diluted. According to Cargill’s survey, 63% of consumers look for an indication of sustainable sourcing on-pack, but only 43% of consumers report they specifically look for a Fair Trade mark.

Frozen seafood maker Gorton’s was recently served with a consumer-led lawsuit challenging a “sustainably-sourced” claim on its tilapia products and, since the term lacks a federal definition, both sides are now left arguing about how it is most commonly interpreted by consumers in court.

In reality, most labels indicating that products are sustainably sourced are coming from Orthodox origins. Regenerative agriculture, which falls under the sustainably sourced umbrella, can be reflected through certifications like Land to Market, ReGen Earth Verified and Regenerative Organic Certified. These certifications assess each step, starting with the farms growing ingredients and accounting for each link in the supply chain to ensure that regenerative practices, which often coincide with organic farming, are maintained as the product makes its way to market.

Regenerative certifications are new to the shelf, all launching within the past two years. This coincides with the rising prominence of the term according to the Rainforest Alliance Certified, another certification program that aims to protect forests and biodiversity from over-farming, among other initiatives. While these practices are not new, the novel idea of attaching a term and certification to traditional growing techniques has raised awareness of the negative impacts of the modern, industrialized approach to conventional farming.

Regenerative ag also often dovetails with upcycling at the farm level when farmers need to plant cover crops or rotate between crops each year to increase biodiversity and reduce pesticide use. In many of these cases, those cover crops go to waste. Brands like Barnana have found secondary uses for those outputs, for example utilizing the fruit of plantain trees previously used only for shade to make its Plantain Crisps line.

What’s next?

The promise of new labels may be bright, but brands may need to ramp up the ways they educate consumers on their commitments. According to Innova Market Insights, 61% of consumers say they try to understand a new eco-friendly label claim when they see one on a brand’s packaging. But consumers also say brands need to be more transparent and offer more guidance on the recyclability and environmental impact of the container itself.

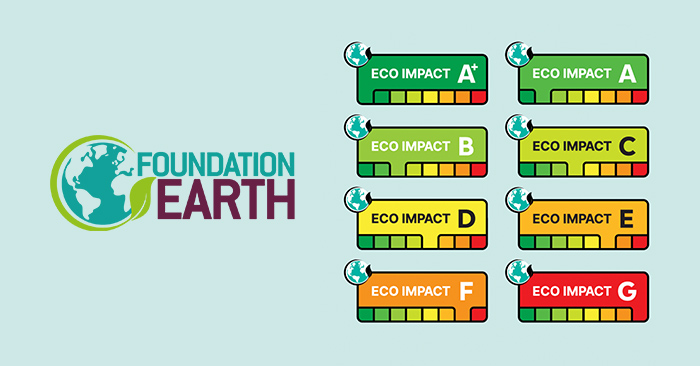

In Europe, eco-scoring system Foundation Earth, backed by Nestlé and U.K. food giant Marks & Spencer, is set to roll out across the E.U. and U.K. this year. Conveying a product’s impact on the environment through a color-coded badge accompanied by a grade from A+ to G on the front of the pack, the certification and scoring process takes farming, processing, packaging and transportation into account to determine the grade – which translates to carbon footprint, water and biodiversity impacts.

There are no set plans to introduce the system stateside, but considering Foundation Earth aims to reduce consumer confusion around labeling through a whole-systems, “farm to shelf” approach, the model could streamline labeling practices in the U.S. by replacing the myriad of badges and buzzwords with a single symbol.

Some states and regulatory agencies are also looking to increase transparency and reduce confusion around sustainability claims as well.

In California, the senate is closing in on emission disclosures with its recently passed Climate Corporate Accountability Act. The legislation requires any company that does business in the state and generates $1 billion or more in gross revenues to disclose all emissions. The SEC is also working on a rule that will require publicly traded companies to disclose carbon emission outputs throughout their supply chain, including when those outputs are generated by a private entity.