Flipping The Script: How To Innovate Like a Corporation

For years, leaders of the biggest packaged food manufacturers have been studying – and, in some cases, acquiring – emerging brands to gain insights on how to “innovate like a startup” with a focus on speed, agility and disruption.

But surely, these large corporations are doing some things well – or, at least, have had to do some things well at some point. We spoke to industry experts about what Big CPG can teach brands at the entrepreneurial level, from product development strategies to mindset.

“What big companies do well is organization and discipline,” said Arnulfo Ventura, senior vice president of strategy at Siddhi Capital and a former PepsiCo executive. “It’s what I see lacking the most amongst early-stage brands.”

Behind some of the most successful launches are rigorous consumer research, lengthy product development cycles and massive marketing budgets – as well as several tactical takeaways for brands of all sizes.

Think Bigger

Predicting which food trends will fade or stick has become increasingly challenging. Rather than jumping on a fad, big companies consider how an idea can meet the long-term needs of a consumer, said Lynn Dornblaser, director of insights and innovation at Mintel.

“What is the special thing about [a trend] that makes it very now? Is it moving one thing from one category into another category that makes it very new and interesting? Is it a flavor? Is it texture?” she said.

Big companies excel at squeezing front-line brands into every conceivable space. An area that grew amid ongoing inflation was co-branded and licensed products, said Joan Driggs, vice president of content and thought leadership at Circana. She pointed to Betty Crocker Cinnamon Toast Crunch baking mixes, which generated $12.7 million in first-year sales, according to the market researcher’s latest New Product Pacesetters report.

“If you look at Cinnamon Toast Crunch, for whatever reason, this cereal brand has so much innovation around it every year,” said Driggs. “This brand has made the leap and is offering new occasions and extending into different parts of the store. That’s really where some of these big brands are showing their strength.”

Cinnamon Toast Crunch’s breakout from the breakfast bowl has spanned pretzel bites, taco shells, stuffed marshmallows, coffee and, most recently, bacon. This month, General Mills and Hormel Foods Corporation introduced a limited-edition Hormel Black Label Cinnamon Toast Crunch Bacon, featuring thick-cut strips “hand-rubbed” with sugar and cinnamon.

“You have to figure out, ‘Where does my brand have permission to play, and where doesn’t it?’” Driggs said. “Will Cinnamon Toast Crunch ever be a beverage? … It certainly plays well in baked goods, and it plays well in different breakfast occasions.”

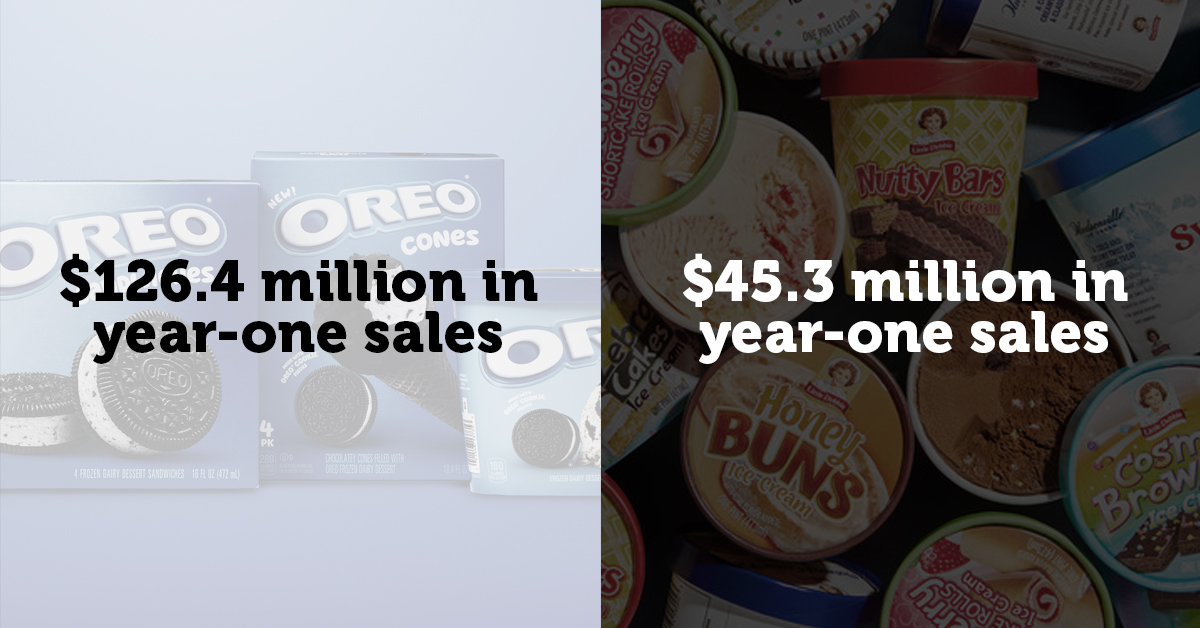

Adding a twist to a familiar food or flavor offers a low-risk entry point – also known as safe experimentation – for consumers. Take Oreo and Little Debbie, whose forays into the freezer case posted $126.4 million and $45.3 million, respectively, in year-one sales. Within the snacking segment, Doritos Minis, Cheetos Minis and Sunchips Minis scooped up $104.5 million in sales, while General Mills Minis – which includes tiny takes on Trix, Reese’s Puffs and Cinnamon Toast Crunch cereals – delivered $63.2 million.

“What they’ve done is they’ve taken their iconic brands and miniaturized them, which is clearly a big theme for 2023 – miniaturization – but that leads to new consumer occasions” such as on-the-go consumption, Driggs emphasized.

Understanding and anticipating consumer needs on a bigger scale can lead to breakthrough products, said Kirsten Sutaria, director of R&D and innovation at SkinnyDipped.

“Many small businesses start because the founders make a product that has attributes that appeal to them or a cause they are passionate about, and while that can be really innovative it isn’t always consumer-centric,” said Sutaria, whose product development career has ranged from startups to global legacy brands.

“While big companies have big budgets to conduct research and invest in data and analytics, emerging brands can emulate this by conducting direct consumer research for feedback, engaging with early adopters and using real-time customer insights to tailor their offerings,” she added.

Emerging brand operators should understand how to communicate a cutting-edge concept to a broader consumer base, Dornblaser said, noting bigger companies take a “softer approach” in how they message lesser-known ingredients like reishi mushrooms.

“Many people might think consumers broadly know what nootropics and adaptogens are, but the reality is most consumers don’t have the foggiest idea,” she said. “For small companies, perhaps the lesson learned is focusing a little less on the functional ingredient and more on the end benefit and what the big picture is.”

Go Slower

“Speed is so embedded in entrepreneurship that it can be challenging to slow down and be intentional,” said Natalie Shmulik, chief strategy and incubation officer at incubator ICNC and The Hatchery. “There is something to be said about taking time to carefully test a profitable concept before investing a significant amount of funds and energy into a new idea.”

Big companies might be accused of appearing less than nimble, but they do their homework in order to avoid unforced errors. That requires time and diligence, said Ventura, a longtime leader and operator in the food and beverage industry. In the mad dash to market, many small brands skip key steps that may result in costly lessons later, he added.

“Is it going to taste great? Have you proof pointed it against quality degradation? Are you even communicating to the consumer the value proposition clearly? Have you thought through where it goes within the store or part of the shelf? It’s hard to shortcut a lot of that stuff,” he said.

In their deliberateness, product development cycles at large companies average 18 to 24 months. Ventura said the “best challenger brands cut that lead time” to 12 months, noting, “if you’re doing it with any kind of rigor, that’s about the right amount of time.”

Part of that process should include gathering buy-in across an organization, which he said can help squash any internal bearishness over whether a new product or line extension makes sense for the company. As CEO of Beanfields and then Alter Eco, Ventura said he collected signatures from the entire team prior to production of a new launch, taking cues from his previous tenure at PepsiCo, where he led corporate sales strategy for the venturing and innovation business unit.

Of course, at small brands, you make do with what you have, Ventura pointed out, noting that “your accountant might not know the first thing about innovation or creative, but they may find spelling errors on the label or packaging.”

Build the Case

The multi-layered approach to big companies means that a lot of ideas are built out only when they can be justified financially and can show long-term viability – something that spur-of-the-moment entrepreneurs aren’t always considering.

That means that at a time when profit is paramount, emerging brands should pause to focus on margins early in the product development process, Sutaria said.

“For every product or platform you’re developing you should have a target for [cost of goods sold] and margins, and if the new innovation doesn’t line up with that or have a clear path to the target, you don’t have a solid business case,” she said. “I have seen many great innovations get killed at larger companies because there isn’t a strong enough business case or path to the target margin.”

While big companies have the advantage of broad, at times international, manufacturing and ingredients, smaller brands are often looking for that one service provider who can help them bring an idea to life. But going a bit slower gives an entrepreneur the chance to build a resilient and redundant supply chain and partner network, Shmulik said.

“These last three years have presented several new challenges around sourcing, manufacturing, and retail exposure,” she said. “Relying on one supplier, co-manufacturer, and/or retailer can create tremendous risk.”

Having limited resources means that good ideas can sometimes slip away more quickly for entrepreneurs, as well.

“Big brands have built strong contingency plans,” she said. “While resources may be limited for startups to work with multiple suppliers or co-manufacturers, conducting the research and knowing what is available is essential to avoid the classic ‘putting all your eggs in one basket.’”