Study Sparks Debate Over Heavy Metals in Dark Chocolate

Both organic and conventional chocolate makers came under fire late last month when a Consumer Reports (CR) study found potentially hazardous levels of lead and cadmium in 28 dark chocolate products. The issue became more complex over the past week when Trader Joe’s and Hershey’s, two of the producers named in the report, were served with class action lawsuits alleging that they misled consumers about the health benefits of the bars by not disclosing the potentially unsafe levels of lead and cadmium.

A total of three lawsuits have been filed in response to the report so far, two against Trader Joe’s and a third naming Hershey’s and portfolio brand Lily’s Sweets as defendants. All three cases were filed in either New York federal or district court.

Following the report’s publication, chocolate makers and industry stakeholders spoke out, criticizing the chemical standard used to quantify CR’s tests, claiming the metric is not intended as a food safety standard. As the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) begins to take a more rigorous look at chemical hazards within the food system, heavy metal content in chocolate may become a priority for regulators.

What did the report find?

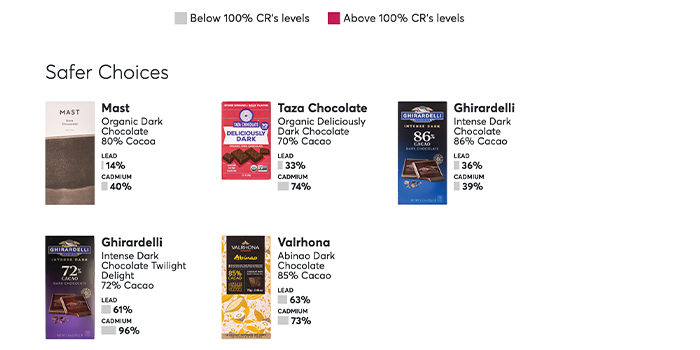

According to CR researchers, all 28 dark chocolate products tested in the study had varying amounts of both cadmium and lead, with 23 containing “concerning levels” and five with relatively low concentrations of both metals.

“For 23 of the bars [tested by CR], eating just an ounce a day would put an adult over a level that public health authorities and CR’s experts say may be harmful for at least one of those heavy metals,” the report states. “Five of the bars were above those levels for both cadmium and lead.”

The report used a standard from California’s Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) which set the maximum allowable dose level (MADL) for lead at 0.5 micrograms – or 0.0005 parts per million (ppm) – and for cadmium at 4.1mcg, or 0.0041ppm.

“Our results indicate which products had comparatively higher levels and are not assessments of whether a product exceeds a legal standard,” the report notes. “We used [the California] levels because there are no federal limits for the amount of lead and cadmium most foods can contain, and CR’s scientists believe that California’s levels are the most protective available.”

While no legal federal limits exist for the overall chocolate category, the FDA has set a threshold for maximum lead contents for candy frequently by small children at 0.1 ppm. The threshold specifically for dark chocolate is 0.15 ppm, a metric that came from a settlement between chocolate industry leaders and corporate accountability organization As You Sow in 2018 over this issue. The settlement also resulted in a three-year-long study, published in August, detailing how lead and cadmium levels in cocoa and chocolate products can be reduced.

The National Confectioners Association (NCA) immediately weighed in on the findings, clarifying that the MADL used for the study is not a food safety standard and that the products included in the report are compliant with “strict quality and safety requirements” and “well under the limits” established by the 2018 settlement.

A spokesperson from Tony’s Chocolonely’s quality and sourcing team also echoed the NCA’s remarks, explaining that trace amounts of heavy metals can be found in chocolate as well as many other foods including vegetables and cereals. The products obtain the naturally-occurring element during the growing process as it is absorbed from soil. The CR study indicated that while this may be the case, contamination from these elements can also occur during the process of drying cacao for processing.

“The conclusion of the CR article was surprising, but it is not surprising that dark chocolate contains substances of lead,” said a spokesperson for Tony’s. “Consumer Report provided a heads up of the publication…[We] communicated that substances of lead found in our dark chocolate are within acceptable limits with the authors of the article, which they unfortunately refrained to include.”

Within the report, the authors included commentary from Alex Whitmore, CEO of Taza, a chocolate brand tested in the study that was found to be one of the five “safer” choices. According to the report, Taza mixes beans from different origins to “ensure” an end product with lower heavy metal levels. For a company like Tony’s or Alter Eco, who have built brands around single-origin beans and close-knit grower networks, mixing beans from vastly different sources is not always a viable option.

Tony’s as well as its chocolate manufacturer, Barry Callebaut, regularly send its products for hazardous chemical testing by an external accredited lab, including lead, said a member of Tony’s quality and sourcing team.

What’s next?

For Tony’s, the company said business will proceed as usual, emphasizing that its chocolate is within the threshold set by the FDA and European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), adheres to the same standards of other food purchased on a regular basis and is safe to consume.

However, with three pending class actions alleging deceptive and misleading business practices, it’s unlikely the issue will be laid to rest anytime soon. The suits also bring a broader issue into focus – how the FDA regulates hazardous chemicals within the food system.

In 2021, the agency launched the Closer to Zero action plan aimed at setting standards to lower the concentration of naturally occurring, but potentially hazardous chemicals in foods often consumed by babies, toddlers and young children. The plan launched after toxic levels of lead and arsenic were detected in a range of cereal-based children’s foods, many of which were later recalled.

Notably, Sultzer Law Group, the firm that brought one of the cases against Trader Joe’s and the other against Hershey’s, has also filed multiple similar suits regarding heavy metals in baby food. The majority of those cases have been dismissed.

The FDA has thus far not indicated if a recall is being explored. Chocolate may fall on the periphery of the agency’s Closer to Zero priorities, but the plan itself will likely have secondary impacts on how the FDA thinks about and prioritizes chemical hazard issues, explained John Johnson, senior counsel at law firm Shook Hardy and Bacon where he specializes in FDA regulatory compliance.

Johnson said that issues like this also mark a shift in the FDA’s focus for the next decade. He claimed that after the Food Safety Modernization Act was passed in 2011, the agency prioritized eliminating biological hazards within the food system. Moving forward, he believes that the FDA’s agenda may take a closer look at chemical-based hazards, like heavy metals, and begin to work through guidance aimed at lowering the presence of those elements in the food supply. The agency released guidance on suitable lead and cadmium levels for cereal-based baby food in 2022.