Kroger/Albertsons vs The FTC: What Happens Next?

As speculated last week, the next challenge for the proposed $24.6 billion merger between Kroger and Albertsons is coming from the federal government.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) today announced it has filed a lawsuit to block the merger in the U.S. District Court for the District of Oregon, alongside a bipartisan group of nine attorneys generals from Arizona, California, the District of Columbia, Illinois, Maryland, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon and Wyoming.

According to the FTC, the commission investigating the merger’s anti-competitiveness unanimously voted (3-0) in favor of filing a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction against the deal, which the agency argues eliminates competition in the grocery industry, and will lead to higher prices for consumers and harm the tens of thousands of workers employed by both corporations.

Even the supermarket’s executives have admitted to the anti-competitiveness of the deal, the FTC claims, highlighting in a release that one executive reacted to the deal by claiming: “you are basically creating a monopoly in grocery with the merger.”

The FTC emphasized that if the deal were completed, the combined companies would operate over 5,000 stores, 4,000 retail pharmacies and employ 700,000 workers across 48 states.

“This supermarket mega merger comes as American consumers have seen the cost of groceries rise steadily over the past few years,” said Henry Liu, Director of the FTC’s Bureau of Competition, in a press release. “Kroger’s acquisition of Albertsons would lead to additional grocery price hikes for everyday goods, further exacerbating the financial strain consumers across the country face today.”

But Albertsons reinforced its stance in a statement today that the merger will “expand competition, lower prices, increase associate wages, protect union jobs, and enhance customers’ shopping experience;” Kroger echoed similar claims.

Grocery Channel Fractures

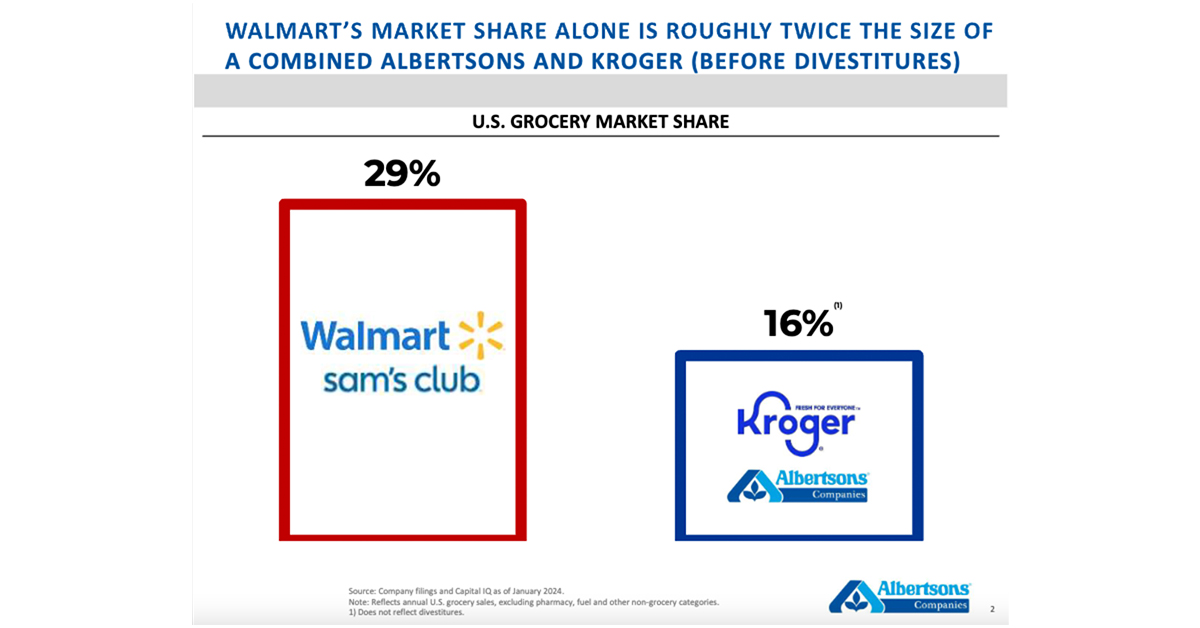

The FTC’s complaint holds that the two companies are direct competitors, but whether that matters in a grocery landscape that now sees non-direct competitors hold a significant share of the market remains a question likely to be debated by the court.

Both Kroger and Albertsons reemphasized their belief that rejecting the deal would harm their ability to compete against multi-channel retailers like Amazon, Walmart and Costco. The companies claim that by merging, the combined entity could offset these aforementioned group’s “growing dominance of the grocery industry” by ensuring local supermarkets can better compete.

Today’s filing reveals that in addition to believing the merger reduces competition, FTC is challenging whether the previously announced divestiture plan with C&S Wholesale Grocers has the potential to be successful and allow the newly divested businesses to hold their own against their former parent organization.

“The combined company committed that no stores, distribution centers or manufacturing facilities will close as a result of the merger, including those divested to C&S Wholesale Grocers,” a Kroger spokesperson said in a statement.

The companies have said they plan to divest 400 stores, and can sell up to 650, to the wholesale and distribution company. The FTC claims the plan itself is “inadequate” and features a “hodgepodge of unconnected stores, banners, brands, and other assets that Kroger’s antitrust lawyers have cobbled together.”

C&S’s current share of the grocery market also remains up for debate. The FTC claims the Piggly Wiggly and Grand Union banner operator runs only 23 supermarkets, and a single retail pharmacy. Media reports have placed C&S’s total retail footprint at 160 locations. Either way, federal regulators believe the proposed divestiture does not create a “standalone business.”

“In areas where there are divestitures, the proposal fails to include all of the assets, resources, and capabilities that C&S would need to replicate the competitive intensity that exists today between Kroger and Albertsons,” the complaint states. “Even if C&S were to survive as an operator, Kroger and Albertsons’s proposed divestitures still do not solve the multitude of competitive issues created by the proposed acquisition.”

Next Steps

If nothing else, the FTC’s suit ensures that any potential timeline for completing the merger will be stretched.

“This is a first step in order to slow things down,” explained Brian Albrecht, chief economist at the International Center for Law & Economics. “[This deal has] already been slowed down a bunch, but [now it is] the court saying they have to slow down.”

Albrecht believes the dispute between the regulator and the retailers must be over a significant number of markets. While there is always a chance that once divested, stores could fail under new ownership – as was the case when Albertsons divested stores to Haggen to appease regulators in its 2014 merger with Safeway – Albrecht, doesn’t believe that is a likely outcome.

He highlighted that it has become commonplace in recent years for grocers to create efficiencies by leaning heavily into vertical integration. Considering C&S specializes in wholesale distribution, he believes those existing operations could give newly divested stores a solid foundation for success.

“Albertsons has been doing it, Kroger has been doing it, Walmart developed their own distribution system, so other companies have shown that this [type of] integration can work and can be efficient,” said Albrecht. “The question is whether it can work wholesaler to grocery store versus what we tend to see which is the store getting more into the wholesale and distribution side.”

Walmart has notably grown to become a leader in grocery since opening its first supercenter store in 1988, which saw it sell groceries for the first time. That same year was also the first, and last time, a supermarket merger has been challenged in court with American Stores and Albertsons’s acquisition of Lucky Stores. That means the last precedent set on competition in the grocery space is nearly 40 years old and came before many of today’s top players had entered the game.

There has been a lot more change to the landscape since then as well. Big box stores, discount chains and even dollar stores have also become grocery shopping venues, shifting how and where consumers buy food. Online grocery shopping has also evolved, albeit in more recent years, to become an important part of the food-buying landscape.

“The number of club warehouses and dollar stores – that type of [store] – has grown 25,000 over the last 25 years, the number of grocery stores has fallen 2,000,” stated Albrecht. “We’ve seen a big upsurge in these things that aren’t traditionally called grocery stores, but clearly have an impact on competition in the market.”

The changes to the market, including the landscape for grocery and the higher prices consumers have faced in recent years, will remain a central feature to both sides’ defense.

Both Kroger and Albertsons emphasized today that they are willing to go to court for the deal. Given the current FTC’s track record, the federal regulator is also expected to put up a fight. That means the merger’s close date could be pushed out well beyond the anticipated August 17 date executives set earlier this year

“We are disappointed that the FTC continues to use the same outdated view of the U.S. grocery industry it used 20 years ago,” a spokesperson for Albertsons said in a statement.

“The merging parties look forward to litigating this action in court so we can deliver the benefits of this merger to communities across America – lower prices, more choices, and more good-paying union jobs for decades to come,” Kroger said in a statement.