Ben & Jerry’s and Tony’s Chocolonely Join Forces Against Cocoa Industry Labor and Supply Chain Issues

Child labor, unfair wages, deforestation and unsustainable sourcing methods have long plagued the global cocoa supply chain, but two social impact-focused companies are joining forces in an attempt to change that narrative.

Under a new partnership announced today, Unilever-owned ice cream maker Ben & Jerry’s will bring Open Chain-sourced cocoa from Tony’s Chocolonely’s “100% Modern Slavery free” network into its pints, beginning the transition in its chocolate ice cream bases and the launch of a new flavor.

“Not only will this partnership see large volumes of cocoa beans sourced via Tony’s Open Chain but collaborating with one of the world’s most-loved social justice companies truly puts our initiative on the map internationally and proves that our way of working is a solution for all players in the cocoa industry,” said Joke Aerts, Open Chain Lead at Tony’s, in a press release.

To further drive awareness, the companies are launching three co-branded products in 2023: a Ben & Jerry’s pint of chocolate ice cream with caramel and chocolate swirls and two Tony’s Chocolonely bars in Strawberry Cheesecake and Dark Milk Brownie flavors.

What’s unique about Tony’s supply chain?

Tony’s Chocolonely opened its doors in 2005 with the goal of building an impact brand that operated in the CPG space, said the company. It established a network of suppliers in the Ivory Coast and Ghana where 60% of the world’s cocoa is grown, and where farmers are all paid the same price per ton for their harvest. That fee, known as the farm gate price, is set annually by each country’s government, respectively, and is contingent on international cocoa prices.

While certified chocolate farmers receive a premium on top of that payment, the sum is still not enough to enable farmers to live above the poverty line, according to Tony’s, and these factors keep farmers living in poverty and propels the cycle of modern slavery and child labor.

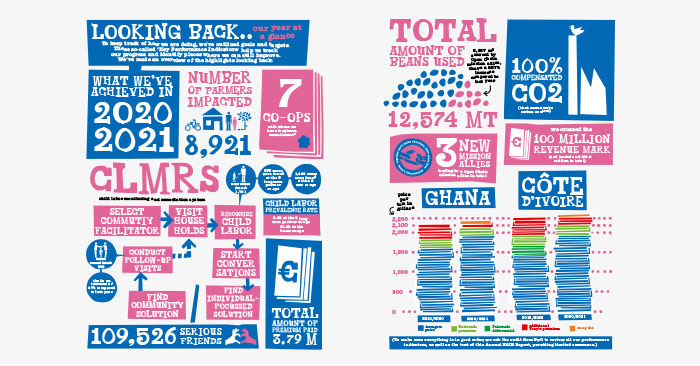

But higher cocoa prices aren’t the only component to fixing the system. Tony’s Open Chain system was developed around five sourcing principles that it believes can induce long term, systemic change. Traceable bean supplies, higher payments for crops, strengthening farms with professional resources and equipment, required five year minimum commitments for higher priced cocoa sales and investments in agricultural skills to enable higher quality and greater production yields are all core aspects of its initiative.

The company estimates that a farmer supported by a professional co-op should be able to produce 800 kilos of cocoa per hectare, yet most only produce between 30% to 40% of that. With the current farm gate price set at $1,088 per ton, Tony’s paid farmers an additional premium of $590 per ton during the 2019/20 growing season which is a combination of its FairTrade premium and an additional sum directly from Tony’s.

Where does Ben & Jerry’s come in?

The ‘mission alliance’ will not only bring Tony’s mission to new aisles, but also will support an expansion of its supplier cooperative network beyond its existing eight farming cooperative partners.

Just last month, Ben & Jerry’s sued parent company Unilever claiming it was undermining its social mission and compromising the integrity of the brand in favor of financial and operational actions regarding its business in Israel. But this social impact decision, which will see the company pay higher fees for its cocoa, seems to have pushed onward without a hitch.

“We began this journey seven years ago, when we first partnered with FairTrade co-ops in [the Ivory Coast], and this is the exciting next step in our cocoa journey,” said Cheryl Pinto, Ben & Jerry’s global head of values-led sourcing, in a press release. “Tony’s Open Chain enables us to combine traceability with sourcing principles that naturally align to Ben & Jerry’s mission.”

What’s next?

Tony’s has emphasized that widespread change will not happen overnight or without the support of large ingredient suppliers and chocolate makers. The company has joined forces with the Child Labour Monitoring & Remediation System (CLMRS) which was co-developed by Nestle and the International Cocoa Initiative (ICI); earlier this year, Nestle also nearly tripled its investments in its cocoa supply chain, committing $1.4 billion by 2030, a portion of which will be used to incentivize farmers to reduce unfair labor practices.

Mondelēz has launched similar initiatives including its Cocoa Life program which focuses on reducing climate change impact, gender inequality, poverty and child labor within the industry with the goal of using sustainably sourced chocolate in all of its products by 2025.

However, those actions have not come without controversy. Last year, eight plaintiffs from Mali filed a class action suit accusing the world’s largest chocolate producers – Nestlé, The Hershey Company, Cargill, Mars, Mondelēz International, Barry Callebaut and Olam International – of using forced child labor. The case was dismissed in June when the judge said the plaintiffs could not show a “traceable connection” between the companies in question and the plantations they had worked on.

While that may be true in a legal sense, the structure of the cocoa supply chain in of itself makes it nearly impossible for plaintiffs to show that connection. Cocoa producers in this region typically harvest, ferment and dry their beans before they are sold to local traders who bring the crop to West African ports to supply international processors and distributors. According to Tony’s, certified and non-certified cocoa beans are all heaped together when they arrive in ports, making the majority of cocoa bean origins virtually untraceable.