What Inflation? Food Prices Have Been Low Since 1992 Says Food Industry Association

It’s an argument so counter to the prevailing inflationary mood that the speakers felt the need to qualify it lest they appear callous, but experts from the Food Industry Association (FMI) argued during a webinar that over the long term, food costs aren’t that high.

Of course, that’s not the consumer view, or the view of the monthly Consumer Price Index report released on Wednesday, which showed what most grocery shoppers already knew; food prices are still going up.

But experts on a Food Industry Association (FMI) webinar Wednesday said that the latest numbers don’t tell the whole story.

“We’re all shoppers, so we can sympathize and empathize with Americans who are confronted with increased prices and occasional out-of-stocks,” noted moderator Heather Garlich, the FMI’s senior vice president, communications, marketing and consumer. “But as we’ll hear from our experts today, the situation is not as dire as shoppers’ perceptions appear.”

The webinar – “Peering Into Food Inflation’s Black Box” – painted a more nuanced picture of rising food prices, one that showed nominal increases in the cost of food relative to inflation over the past three decades.

So why are consumers feeling the pain so acutely right now? Structural flaws in the food system have been exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on supply chains and consumer shopping trends, according to FMI.

The conversation between Andy Harig, FMI vice president of tax, trade, and sustainability, and Dr. Ricky Volpe, Associate Professor of Agribusiness at Cal Poly University, attributed the current record inflation in the food industry to stress in four main areas: labor, transportation, packaging and energy/fuel costs.

Supply chain problems have been a persistent challenge for retail throughout the pandemic in terms of sourcing and transporting products, but so has companies’ ability to staff all the pieces of the supply chain. Attracting, training and maintaining a steady labor force was a costly process even before lockdowns forced some production to temporarily halt.

The American Trucking Association reported in October 2021 that the industry faced a shortage of about 80,000 drivers last year, with that number expected to more than double by 2030. This driver shortage has both caused and exacerbated gridlock at shipping ports, slowing the movement of ingredients, packaging materials and products.

Since 2000, port traffic has increased 238%, with long-haul trucking rates increasing 68% during that time period, according to FMI data.

Grocery shopping has evolved over the course of the pandemic and into the current high inflationary period. According to FMI data, the current average household spending on groceries is $136 per week, down from $161 per week at the height of the pandemic and $148 on average in February 2022. It’s a seemingly discordant note played against inflation; one that FMI’s experts are still poring over. One potential insight was that lower-income households could be cutting back on groceries.

Although most economists are hesitant to characterize the current period as a recession, Harig said this data point is somewhat unique when compared to the Great Recession.

“For example, at the beginning of the financial crisis in 2008, consumers drastically cut back on their grocery spending overall. Currently shoppers are still spending, but they have instead been looking for more value: trading down to less expensive products or increasingly trying more affordable store brands,” Harig said.

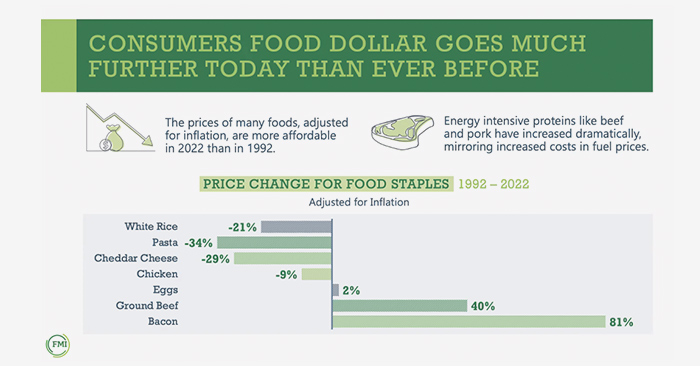

One FMI argument bound to be cold comfort to consumers: the actual price of food items has been relatively “muted” since the late 1990s, Volpe reported.

“I’m a shopper. You’re a shopper. We’re all feeling it, right?” he said. “But these food prices that are really increasing in a meaningful way relative to the value of the US dollar are fairly concentrated and shoppers do still have a lot of options for acquiring grocery basket if they need to, or if they so wish, that really hasn’t increased in price that significantly relative to 10, 20, 30 years ago.”

“A lot of that has to do with our success in importing a wide variety of foods to sort of augment and supplement our foods and make food availability less seasonal,” Volpe said.

Incorporating this long view, Volpe stressed, the inflated food prices are largely restricted to meat and dairy items. According to FMI’s data, the price of many staple items is either flat or even down – when it’s adjusted for inflation over a 30-year period. The price of eggs, he noted, is only up 2% over that period, while chicken is down -9%, and pasta is down -34%.

In essence, the success of global trade has helped keep food inflation at bay; when global trade slowed significantly during the pandemic, prices skyrocketed.

Food Prices Shooting Up Like Rockets, Coming Down Like Feathers

Even when inflation does begin to decelerate, the impact on food prices won’t be immediate, however.

Retail food prices in the U.S. are “relatively sticky,” Volpe said, as stores and manufacturers are typically reluctant to change their prices even when there is positive news on gas prices or crop yields.

“Changing prices for a retailer that carries 35, 40, 45,000 products is expensive and it’s a complex undertaking,” he said. “To reduce prices, even a little bit, even nominally, is going to be an expensive proposition – especially given that inflationary costs continue to trend upward over time even in normal periods.”

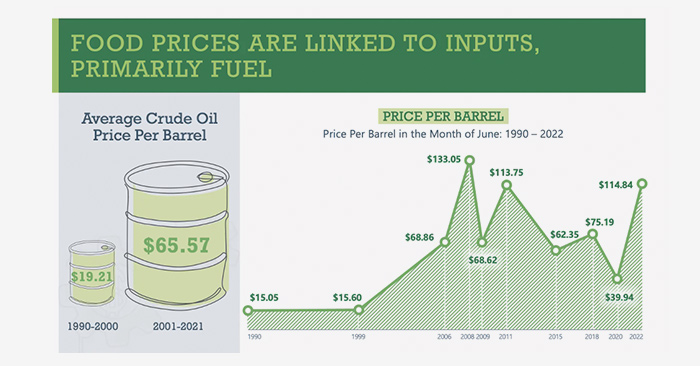

On the whole, innovation in food production has kept prices relatively stable with the exception of energy-intensive products like beef and pork. These products are often more susceptible to the fluctuations in the energy market because raising animals requires significant investments of time and overhead.

Volatility in the energy market over the last two decades has created instability in pricing across all categories of food, Harig said.

“Predictability is a friend to food companies of all stripes,” Volpe added. “Being able to predict demand, being able to predict costs, being able to predict the availability of inputs…it becomes very easy to see why surging energy prices require manufacturers and retailers to tip those prices up.”

Although commodities such as cereals and cooking oils are expected to remain pressured due to the instability in Ukraine, Volpe was confident that there will be some relief coming in 2023.

“I think we’re still going to be a tick or two above normal. But far lower than what we’re seeing in 2022 but not quite back there yet.”